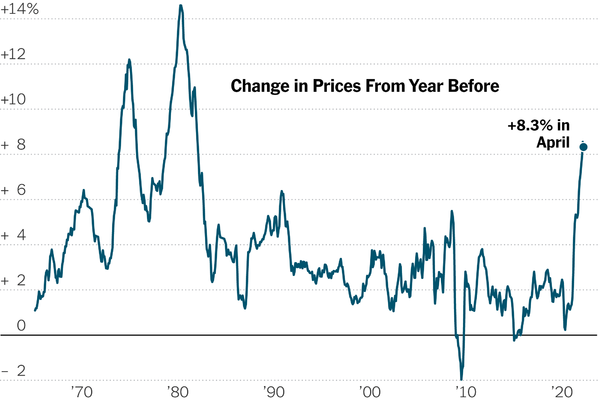

Inflation moderated on an annual basis for the first time in months in April, but the 8.3 percent annual Consumer Price Index increase remained uncomfortably rapid — and a closely watched index that subtracts volatile food and fuel costs actually accelerated.

The takeaway was that the pressures that have kept inflation elevated for months remain strong, a challenge for households who are trying to shoulder rising expenses and for the White House and Federal Reserve as they try to put the economy on a steadier path.

Inflation is beginning to moderate on an annual basis — it had climbed by an even-quicker 8.5 percent in March. The April slowdown was the first cooling in months, and it came partly because gas prices dropped lower last month and partly because of a statistical quirk. Yearly price increases are now being measured against elevated price readings since last spring, when inflation started to take off. The high base makes annual increases look less severe.

The reality that annual inflation has possibly peaked will give the White House and Fed a positive talking point and a dose of comfort. But the good news is undercut by the fact that the so-called core price measure — the one that takes out grocery and gas costs — picked up 0.6 percent in April from the prior month, faster than its 0.3 percent increase in March. Central bankers and economists closely watch that measure as they try to gauge where inflation is headed.

Policymakers have a long way to go to bring price increases down to more normal and stable levels, and Friday’s report is likely to keep them focused on trying to slow inflation that is still lingering near its fastest pace in 40 years.

“There’s not much to reassure the Fed in this release,” Brian Coulton, chief economist at Fitch, wrote in a research note following the report.

Economists do expect price increases to slow somewhat this year: The question is how much and how quickly they will come down. Many analysts expect to see slower price increases or even outright price cuts on many goods, but such forecasts look increasingly uncertain. Lockdowns in China and the war in Ukraine threaten to exacerbate supply shortages for semiconductor chips, commodities and other important products.

“There are persistent issues in supply chains,” said Matthew Luzzetti, chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. “And the most recent developments have not been positive.”

The outlook for the car market, for instance, remains unclear as there are some signs that supply shortfalls for used vehicles are easing, but chip shortages linger and companies continue to struggle to finish building vehicles.

Used cars and trucks declined in price in April compared to the prior month, though less than they had dropped the prior month. Car parts had declined in price in March but summarized their monthly increase in April. New car prices also accelerated after a lull, climbing by 1.7 percent from the previous month.

Services prices are now increasing quickly, as rents climb rapidly and as worker shortfalls lead to higher wages and steeper prices for restaurant meals and other labor-intensive purchases. If that continues, it could keep inflation elevated even as supply problems are resolved.

Rents picked up by 0.6 percent in April from March, and a measure housing costs that uses rents to estimate the cost of owned housing climbed by 0.5 percent, up from 0.4 percent the prior month. The pickup in housing costs is an especially big deal, because they make up about a third of the overall inflation index.

“Domestically-generated inflationary pressures remain strong,” Andrew Hunter, senior US economist at Capital Economics, wrote following the report.

As inflation risks remaining high, the Fed is lifting interest rates to try to keep inflation from galloping out of control in a lasting way.

After a full year of unusually rapid price increases, household and investor expectations for future price increases have been creeping higher, which could help to perpetuate fast price gains as households and businesses adjust their behavior, asking for bigger raises and charging more for goods and services .

Fed policymakers lifted their main policy interest rate for the first time since 2018 in March, then followed that up with the biggest increase since 2000 at their meeting last week.

By making it more expensive to borrow money, officials are hoping to slow rapid spending and hiring, which could help supply to catch up with demand. As the economy returns to balance, inflation should come down.

Central bankers are hoping that their policies will temper economic growth without actually pushing unemployment up or plunging America into a recession. But officials have acknowledged that letting the economy down gently will be difficult, and have suggested that they will be willing to inflict economic pain if that is what it takes to tackle high inflation.