Was acclaimed keyboardist Bernie Worrell merely a hired gun for George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic — or was he a key creator entitled to a stake in royalties?

The question may at last get resolved before a judge. In a lawsuit filed Tuesday in Detroit federal court, Worrell’s estate contends the late musician was never properly compensated for his performances and collaborative work on hundreds of P-Funk and Clinton tracks, including hits such as “One Nation Under a Groove,” “Flash Light” and “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof off the Sucker).”

Defendants include Clinton and his Southfield company Thang Inc., along with Warner Brothers Records and Universal Music, which have arrangements with Thang to release Parliament-Funkadelic recordings.

The suit could formally settle the role played by Worrell — and other P-Funk musicians — in masterminding the groups’ trailblazing work, which blended funk, rock and R&B in a free-spirited musical brew. The rhythm-heavy music, recorded in Detroit, went on to become one of the most-sampled bodies of work as hip-hop blossomed in the ’80s.

A representative for Clinton did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

More music: Stevie Wonder gets honorary doctorate at Wayne State University commencement

Litigation has been a long, thorny side story in the Clinton and P-Funk saga, including court battles involving copyrights, record labels, publishers and even defamation. But Tuesday’s filing is the first to drill deep into the role of Parliament and Funkadelic’s musicians: Were they integral contributors, or simply making works-for-hire under Clinton’s orchestration?

The estate’s attorney said unless there was an explicit agreement otherwise — and Clinton has denied such a contract — then Worrell should be considered a co-creator with a copyright interest in the recordings he performed on and cowrote.

“Trying to predict what Clinton might say is a fool’s errand, but I don’t think there’s any dispute about this,” said the attorney, Daniel Quick, of Dickinson Wright in Troy. “Worrell was a very recognized musician and contributor.”

Tuesday’s filing includes a “partial” list of about 350 tracks the estate contends Worrell was integral in creating.

It alleges that Clinton engaged in a “continued pattern of deceit” with Worrell and other Parliament-Funkadelic musicians.

“He would make oral promises to band members or manipulate them into giving up rights in order to receive payment,” the suit reads.

Worrell was 72 when he died at his Washington state home in June 2016 following a cancer battle. His widow, Judie Worrell, initiated the suit.

[ Looking for more music coverage? Download our app for the latest ]

The complaint contends that Clinton, through Thang Inc., pocketed all Parliament and Funkadelic royalties and advances rather than share them with “the other musicians, artists and producers who collaborated with him to write, create and record the music.”

Clinton, founder and frontman of the groups, has insisted his P-Funk musicians amounted to sidemen, akin to members of a big-band orchestra.

At issue in Worrell’s case is a 1976 contract he said he was offered by Thang outlining a royalty arrangement for his work on the records. Worrell signed the deal, and Tuesday’s filing says he was led to believe Clinton had signed as well.

In a 2019 deposition, Clinton said he had not actually signed the 1976 document.

The Worrell estate initially sued Clinton in New York in 2019. The New York Supreme Court dismissed the case last year, citing the state’s “dead man statute” that limits testimony involving a deceased plaintiff. Because Clinton declared he had not signed a deal with Worrell, the court ruled there was no contract to rule on.

The new Detroit suit says Clinton’s 2019 denial of a signed deal was “a greed-driven attempt to get away without sharing any royalties or earnings from (works) that Clinton and Mr. Worrell created together.”

The estate contends that if Clinton’s claim is correct—there was no binding contract spelling out Worrell’s terms—then the keyboardist was in fact entitled to joint ownership of the Parliament and Funkadelic works.

In Tuesday’s filing, Worrell’s estate says Detroit is a proper venue for the case because P-Funk’s music in the 1970s was created in the city, recorded at studios such as United Sound, Tera Shirma and Artie Fields.

Clinton lived in Brooklyn in Michigan’s Irish Hills area at the time.

Worrell’s estate is seeking a declaration that the late keyboardist was a co-creator of the recordings in question along with an accounting of record sales and potential royalties. Damages would be determined at trial.

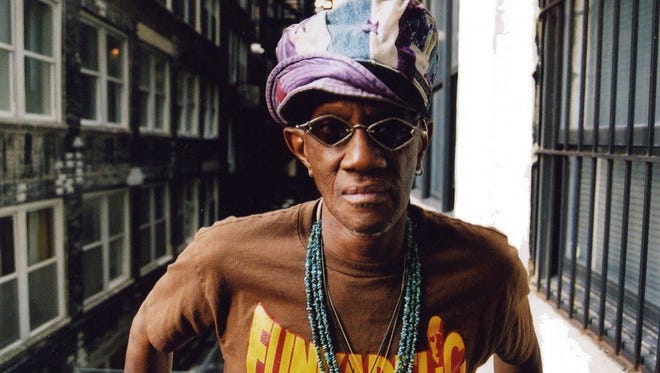

The New Jersey-born Worrell, who studied piano at New York’s Juilliard School and was an early adopter of the Moog synth, played with Parliament and Funkadelic from the early ’70s into the early ’80s. He remained active through his cancer diagnosis in 2016, playing with the Talking Heads, Gov’t Mule, Mos Def and others.

Tuesday’s filing cites a 2021 essay by a music scholar who wrote that the “extraterrestrial soundscape (Worrell) pioneered with his Moog synthesizers not only created P-Funk’s signature sound but functioned as the glue holding the multifarious ensemble together.”

Quick said the Worrell case could pave the way for other Parliament and Funkadelic musicians to stake their own interests in the catalogue.

“I only represent Mr. Worrell’s estate, but I would be shocked if this doesn’t open the door for other musicians to come forward and assert some of their claims,” the attorney said.

Contact Detroit Free Press music writer Brian McCollum: 313-223-4450 or [email protected].